Unix shell basics

Week 2 – Lecture C

1 Introduction

1.1 Context & overview

You’ll be using the Unix shell very regularly throughout the rest of this course. This is the first of several lectures that focus on learning to work in it. We’ll start with a conceptual introduction, and then you’ll take your first steps in the Unix shell!

1.2 Learning goals

In this lecture, you’ll learn:

- What the Unix shell is and what you can do with it

- Why it can be beneficial to use a command-line interface in general and the shell specifically

- How Unix commands are stuctured

- How to navigate around your computer with Unix commands

2 The Unix shell

2.1 Some terminology and concepts

Unix-based (or Unix-like) operating systems include MacOS and Linux but not Windows. For scientific computing, Unix-based operating systems are generally preferable. Linux specifically, while not as familiar to the general public, is what supercomputers like those of OSC, and most servers throughout the world, run on.

Don’t be alarmed if you have a Windows laptop/desktop. Certainly for the purposes of this course, and in principle for your other research, your computer can run on any operating system, because you can connect to OSC and do your work there.

This session introduces the “Unix shell”. How does that relate to some other terms you may have heard of? Let’s run by these terms going from more general ones to more specific ones:

| Term | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Command Line / Command Line Interface (CLI) |

A user interface where you type commands rather than clicking-and pointing like you would in a Graphical User Interface (GUI). This “interface” can be from anything from a specific bioinformatics program to your computer’s operating system. |

| Shell | A more specific and technical term for a command line interface to your computer |

| Unix shell | The type of shell found on Unix-based (Linux + Mac) computers |

| Bash | A specific Unix shell language (the most common one and the one we’ll use) |

Also related is the word terminal: the program/app/window in which the shell is run. A general observation is that while all these terms are not synonyms, they are in practice often used interchangeably.

2.2 Why use the Unix shell?

The Unix shell can be used for a wide variety of tasks, from “file browser” functionality to running specialized software.

The Unix shell has been around for a long time and may seem a bit archaic. But astonishingly, a system largely built decades ago in an era with very different computers and datasets has stood the test of time, and the ability to use it is a crucial skill in computational biology.

Using the Unix shell rather than programs with GUIs has some of the general advantages of using code we’ve discussed:

- Automation and fewer errors

The shell allows you to repeat and automate tasks easily and without introducing errors. - Reproducibility

When working in the shell, it’s straightforward to keep a detailed record of what you have done.

There are also specific reasons to use the Unix shell as opposed to (other) coding languages like R and Python:

- Software needs

Many programs used for omics data analysis have a CLI and are most easily run from the Unix shell. - Viewing and processing large files

Shell commands are excellent at viewing and processing large, plain-text files, which are common in omics data. - Efficiency

Built-in shell tools are often faster in terms of coding and processing time, especially for simpler tasks. - Remote computing – especially supercomputers

When doing remote computing, your point of entry is commonly the Unix shell.

3 First steps in the shell

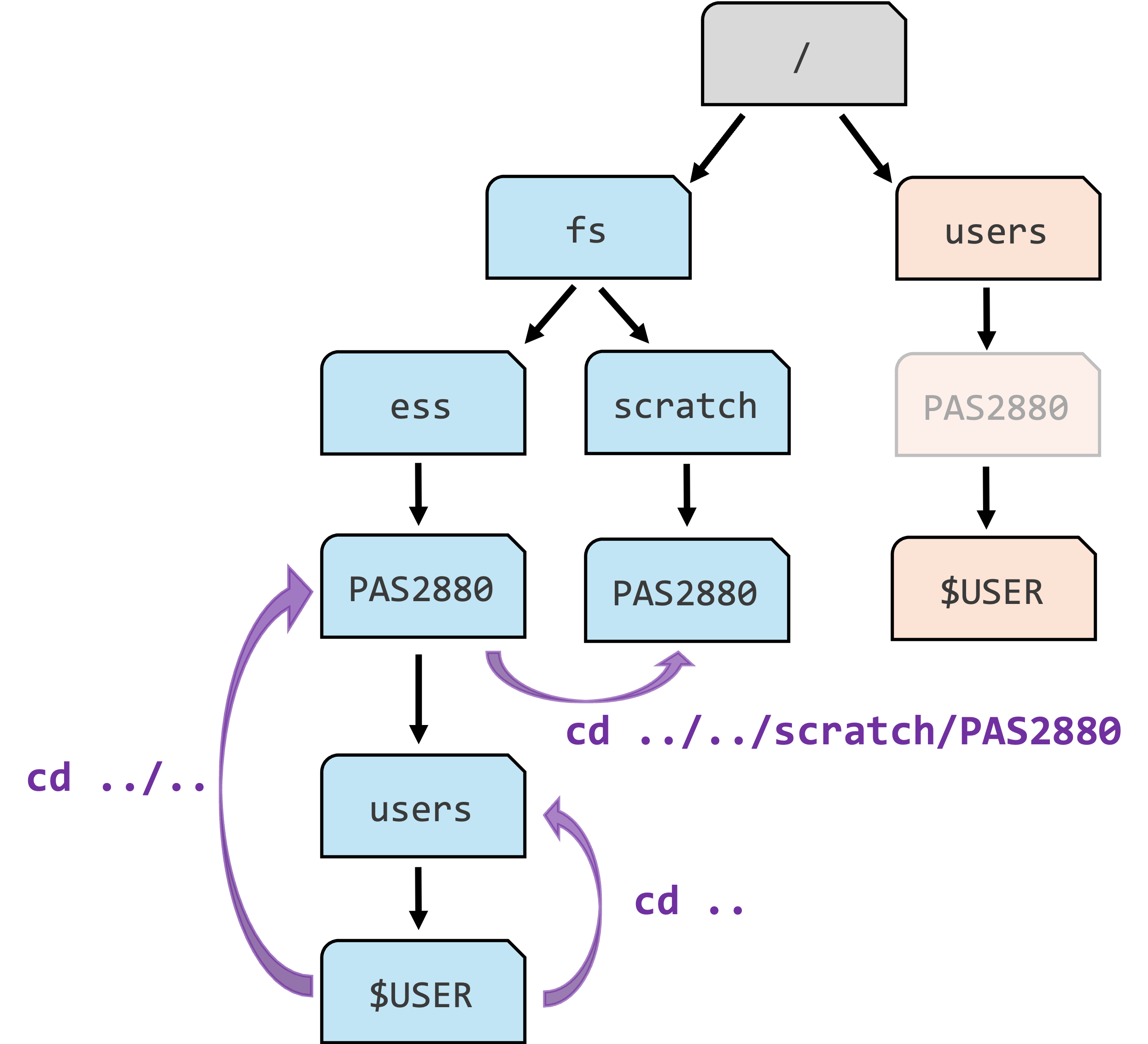

You should already have a VS Code session with a Unix shell open! If not, click here to see instructions.

- Log in to OSC’s OnDemand portal at https://ondemand.osc.edu

- In the blue top bar, select

Interactive Appsand near the bottom, clickCode Server - Fill out the form as follows:

- Cluster:

pitzer - Account:

PAS2880 - Number of hours:

2 - Working Directory:”

/fs/ess/PAS2880/user/<username>(replace<username>with your actual user name) - App Code Server version:

4.8.3

- Cluster:

- Click

Launch - Click the

Connect to VS Codebutton once it appears - In VS Code, open a terminal by either:

- Clicking =>

Terminal=>New Terminal - Using the keyboard shortcut Ctrl+`

- Clicking =>

3.1 The shell’s prompt

Inside your terminal, the “prompt” indicates that the shell is ready for a command. What is shown exactly varies across shells and can also be customized, but our prompts at OSC should show something like this:

[jelmer@p0362 jelmer]$ Which represents the following pieces of information:

[<username>@<node-name> <working-dir>]$The <working-dir> part only shows the name of the directory you are directly located in (e.g. jelmer) rather than the entire path (e.g. /fs/ess/PAS2880/users/jelmer).

You type your commands after the dollar sign $, and then press Enter to execute the command. When the command has finished executing, you’ll “get your prompt back” and can type and execute a new command.

Code-formatted text between

<and>(such as<username>above) is commonly used to indicate not literal code but something that should be be replaced (such as by your personal user name in the<username>example).OSC prints welcome messages and storage quota information when you open a shell. To reduce the amount of text on the screen, I will clear the screen now, and regularly throughout. This can be done with the keyboard shortcut Ctrl+L.

If you see a ~ as the working-dir-part of your prompt, you are instead in your Home directory in /users/ and you will need to go to /fs/ess/PAS2880/users/<user> instead. To do so: click File > Open Folder in VS Code and then type/select that dir. When you then open a Terminal again, the correct dir should be displayed.

3.2 A few simple commands

The Unix shell comes with hundreds of commands: small programs that perform specific actions1. Let’s start with a few simple commands:

The

datecommand prints the current date and time:dateThu Sep 02 13:58:19 EST 2025The

pwd(Print Working Directory) command prints the path to the directory you are currently located in:pwd/fs/ess/PAS2880/users/jelmerThe

echocommand simply prints the text you provide it with, typically between double quotes “ 2.echo "Welcome to PLNTPTH 5006"Welcome to PLNTPTH 5006

All the above commands provided us with some output. That output was printed to screen, which is the default behavior for nearly every Unix command.

Does echo seem useless, or can you think of ways in which it could be useful? (We’ll get back to this later.)

4 Options, arguments, and help

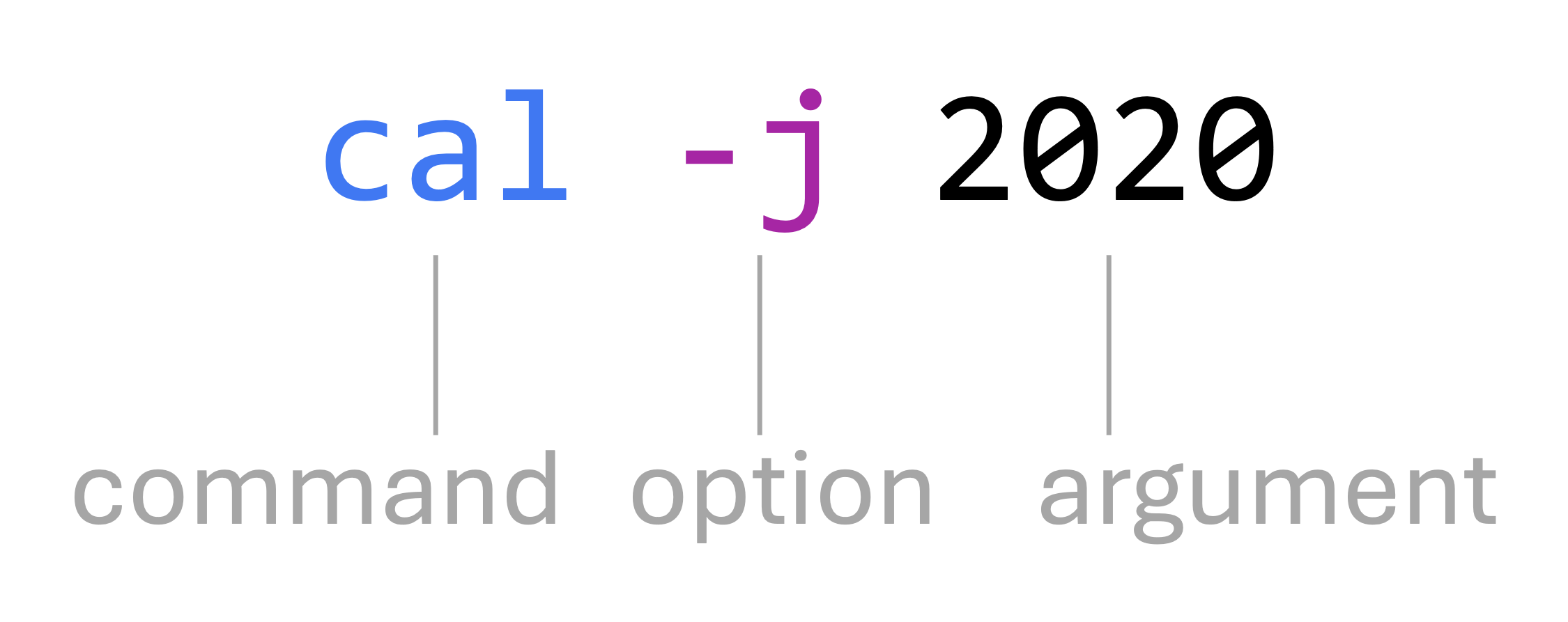

4.1 The cal command — and options & arguments

The cal command is another example of a command that simply prints some information to the screen, in this case a calendar. It’s not a particularly useful command in this day and age, but we’ll use it as a low-stakes example to learn about command options and arguments.

Just running cal will print a calendar for the current month:

cal September 2025

Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa

1 2 3 4 5 6

7 8 9 10 11 12 13

14 15 16 17 18 19 20

21 22 23 24 25 26 27

28 29 30Examples of using command options

Use the option -j (a dash - and then a j) to instead print a Julian calendar, which has year-wise instead of month-wise numbering of days:

# Make sure to leave a space between `cal` and `-j`!

cal -j September 2025

Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat

244 245 246 247 248 249

250 251 252 253 254 255 256

257 258 259 260 261 262 263

264 265 266 267 268 269 270

271 272 273Use the -3 option to show 3 months (adding the previous and next month):

cal -3 August 2025 September 2025 October 2025

Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa

1 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

10 11 12 13 14 15 16 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 12 13 14 15 16 17 18

17 18 19 20 21 22 23 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 19 20 21 22 23 24 25

24 25 26 27 28 29 30 28 29 30 26 27 28 29 30 31

31 You can use multiple options at once – for example:

cal -j -3 August 2025 September 2025 October 2025

Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat

213 214 244 245 246 247 248 249 274 275 276 277

215 216 217 218 219 220 221 250 251 252 253 254 255 256 278 279 280 281 282 283 284

222 223 224 225 226 227 228 257 258 259 260 261 262 263 285 286 287 288 289 290 291

229 230 231 232 233 234 235 264 265 266 267 268 269 270 292 293 294 295 296 297 298

236 237 238 239 240 241 242 271 272 273 299 300 301 302 303 304

243 To save you some typing, options can be “pasted together” like so:

# [Output not shown - same as above]

cal -j3#

Any text that comes after a # is considered a comment instead of code! Comments are not executed but are ignored by the shell:

# This entire line is a comment - you can run it and nothing will happen

cal # If you run this line, 'cal' will be executed but everything after the '#' is ignoredOptions summary

Options are specified with a dash - (or two dashes --, as you’ll see later). The examples so far have involved the kind of option that is also called a flag, which changes functionality in an ON/OFF way, such as:

- Turning a Julian calender display on with

-j - Turning a 3-month display on with

-3.

We’ll see more complex types of options later. Generally speaking, options change the behavior of a command.

Arguments

Arguments typically tell a command what to operate on. Most commonly, these are file or directory paths. Admittedly, cal is not the best illustration of this pattern — when you give it one argument, this is the year to show a calendar for:

cal 2020 2020

January February March

Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa

1 2 3 4 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

5 6 7 8 9 10 11 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 8 9 10 11 12 13 14

12 13 14 15 16 17 18 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 15 16 17 18 19 20 21

19 20 21 22 23 24 25 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

26 27 28 29 30 31 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 29 30 31

# [...output truncated, entire year is shown...]You’ll see examples of commands operating on files or dirs soon. Finally, you can also combine options and arguments:

cal -j 2020 2020

January February

Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat

1 2 3 4 32

5 6 7 8 9 10 11 33 34 35 36 37 38 39

12 13 14 15 16 17 18 40 41 42 43 44 45 46

19 20 21 22 23 24 25 47 48 49 50 51 52 53

26 27 28 29 30 31 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

# [...output truncated, entire year is shown...]To summarize how command arguments differ from options — arguments…

- usually tell the command what to operate on, instead of changing how it operates

- are not preceded by

-and a letter (or--and a keyword) - if options and arguments are combined, arguments go after options3.

4.2 Getting help

Many Unix commands have a -h option for help, which usually gives a concise summary of the command’s syntax, such as its available options and arguments:

cal -h

Usage:

cal [options] [[[day] month] year]

Options:

-1, --one show only current month (default)

-3, --three show previous, current and next month

-s, --sunday Sunday as first day of week

-m, --monday Monday as first day of week

-j, --julian output Julian dates

-y, --year show whole current year

-V, --version display version information and exit

-h, --help display this help text and exitIn this case, we learn that each option to cal can be referred to in one of two ways:

- A short-form notation: a single dash followed by a single character (e.g.

-s) - A long-form notation: two dashes followed by a keyword (e.g.

--sunday)

man command (Click to expand)

An alternative way of getting help for Unix commands is with the man command:

man calThis manual page often includes a lot more details than the --help output, and it is opened inside a “pager” rather than printed to screen: type q to exit the pager that man launches.

Exercise: Interpreting the help output

Look through the options listed when you ran

cal -h, and try an option we haven’t used yet. (You can also combine this new option with other options, if you want.)Click to see a solution

- To print a calendar with Monday as the first day of the week (instead of the default, Sunday):

cal -mSeptember 2025 Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30Try using one or more options in their “long form” (with

--). Can you think of an advantage of using long form over short form options?Click to see a solution

For example:

cal --julian --mondaySeptember 2025 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 244 245 246 247 248 249 250 251 252 253 254 255 256 257 258 259 260 261 262 263 264 265 266 267 268 269 270 271 272 273The advantage of using long options is that they are less cryptic and more descriptive. Therefore, it is much more likely that any reader of the code (including yourself next week) will immediately understand what these options are doing.

Note that long options cannot be “pasted together” like short options.

5 Environment variables

You may be familiar with the concept of variables from previous experience with perhaps R or another language. Either way, variables can hold values and other pieces of data, and they are essential in coding.

While you can create variables yourself, environment variables are pre-existing variables that have been automatically created by the computer. Two examples are:

$HOME, which contains the path to your Home directory$USER, which contains your user name

Note that in the Unix shell, variables are always referenced using a leading $. This helps you recognize them as variables. Additionally, if you want to print the values of variables, you need the echo command:

echo $HOME/users/PAS0471/jelmerecho $USERjelmer Exercise: environment variables and echo

Using an environment variable, get the Unix shell to print Hello, my name is <username> (e.g. Hello, my name is natalie) to the screen.

Click for the solution

# (This would also work without the " " quotes)

echo "Hello, my name is $USER"Hello, my name is jelmer7 Keyboard shortcuts

Using keyboard shortcuts help you work much more efficiently in the shell. Here are some of the most useful ones:

Command history —

Up/Downarrow keys to cycle through your command history.Tab completion — The shell will auto-complete partial commands or file paths when you press Tab.

Cancel/stop/abort — If your prompt is “missing”, the shell is still busy executing your command, or you typed an incomplete command. To abort, press Ctrl+C and you will get your prompt back.

Exercise: canceling

To simulate a long-running command that you may want to abort, we’ll use the sleep command, which makes the computer wait for a specified amount of time before it gives your prompt back (or, e.g. moves to the next command in the context of a script).

Run the below command and instead of waiting for the full 60 seconds, press Ctrl + C to get your prompt back sooner!

sleep 60sAs another example of a situation where you might have to use Ctrl + C, simply type an opening parenthesis ( and press Enter:

(When you do this, nothing is executed and you are not getting your prompt back: you should see a > on the next line. This is the shell wanting you to “complete” you command. Why would that be?

Click to see the solution

This is an incomplete command by definition because any opening parenthesis should have a matching closing parenthesis.Press Ctrl + C to get your regular prompt back.

Exercise: Tab completion & command history

Type

/fand press Tab (will autocomplete to /fs/)Add

e(/fs/e) and press Tab (will autocomplete to /fs/ess/).Add

PAS(/fs/ess/PAS) and press Tab. Nothing should happen: there are multiple (many!) options.Press Tab Tab (i.e., twice in quick succession) and it should say:

Display all 619 possibilities? (y or n)Type

nto answer no: we don’t need to see all the dirs starting withPAS.Add

288(/fs/ess/PAS288) and press Tab twice in quick succession (a single Tab won’t do anything): you should see at least four dirs that start withPAS288.Add

0so your line reads/fs/ess/PAS2880. Press Enter. You will get the following output, which is an error. Can you think of any reason why this you may have gotten an error here?bash: /fs/ess/PAS2880/: Is a directory

Click to see the solution

Basically, everything you type in the shell should start with a command. Just typing a path will not make the shell print some info about, or the contents of, this dir or file. Instead, since a path is not a command, you will get an error.Press ⇧ to get the previous “command” back on the prompt.

Press Ctrl+A to move to the beginning of the line at once.

Add

cdand a space in front of the dir, and press Enter again.cd /fs/ess/PAS2880/

(Note that even on Macs, you should use Ctrl instead of switching them out for Cmd as you may be used to doing – though in some cases, like copy/paste, both keys work).

| Shortcut | Function |

|---|---|

| Tab | Tab completion |

| ⇧ / ⇩ | Cycle through previously issued commands |

| Ctrl+C | Copy selected text |

| Ctrl+V | Paste text from clipboard |

| Ctrl+A / Ctrl+E | Go to beginning/end of line |

| Ctrl+U /Ctrl+K | Cut from cursor to beginning / end of line |

| Ctrl+W | Cut word before cursor |

| Ctrl+Y | Paste (“yank”) text that was cut with one of the shortcuts above |

| Alt+. / Esc+. | Retrieve last argument of previous command (very useful!) (Esc+. for Mac) |

| Ctrl+R | Search history: press Ctrl+R again to cycle through matches, Enter to put command in prompt. |

| Ctrl+C | Cancel (kill/stop/abort) currently active command |

| Ctrl+D | Exit (a program or the shell, depending on the context) (same as exit command) |

| Ctrl+L | Clear the screen (same as clear command) |